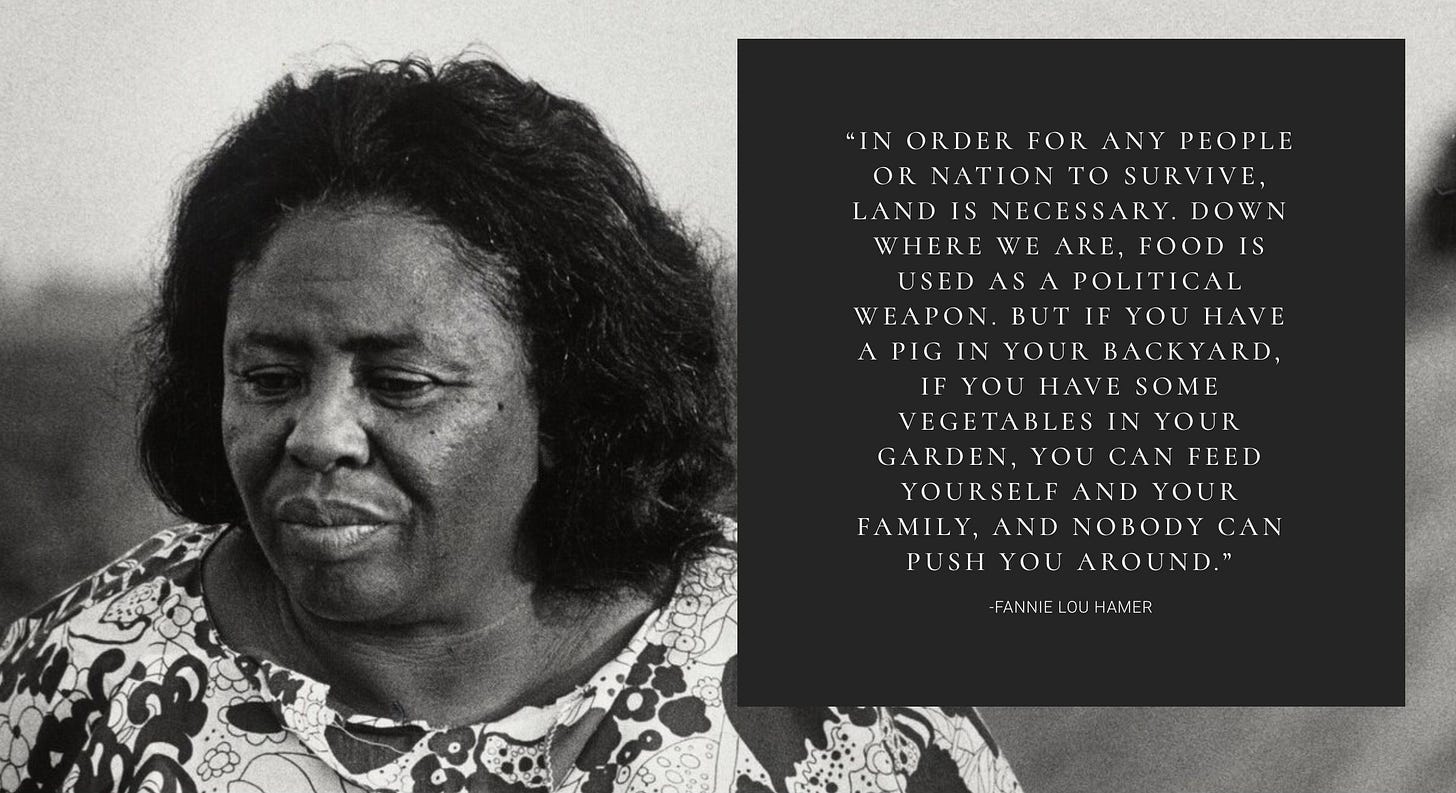

Fannie Lou Hamer and the Freedom Farms Cooperative (1967)

Black History Through the Lens of Liberation

Let this song play as you read this article. Allow yourself to hear and feel her rhythm as you learn more about her, and her vision for us all, and get curious.

When you think of liberation, do you imagine planting seeds and harvesting crops? Fannie Lou Hamer did. She knew that freedom wasn’t just about voting rights or marching in protests—it was about access to food, land, and the ability to provide for yourself and your community. The story of Hamer and the Freedom Farms Cooperative is a blueprint for liberation rooted in collective care, economic independence, and reclaiming what white supremacy sought to withhold from Black people: land and sustenance.

This lesson isn’t just about farming; it’s about the revolutionary act of ensuring that communities can thrive without having to depend on systems designed to oppress them.

Fannie Lou Hamer: From Sharecropper to Freedom Fighter

Born in 1917 in Montgomery County, Mississippi, Fannie Lou Hamer was the youngest of 20 children in a family of sharecroppers. Her life was shaped by the oppressive conditions of the Jim Crow South, where Black farmers were routinely exploited through labor systems designed to keep them in poverty.

Hamer’s activism began in the early 1960s when she joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and became a vocal advocate for voting rights. Her famous declaration, “I’m sick and tired of being sick and tired,” became a rallying cry for the movement. But Hamer understood that political rights weren’t enough. True liberation meant addressing the root causes of poverty, hunger, and landlessness.

She knew that to dismantle white supremacy, Black communities needed land ownership and economic independence. And so, in 1967, she founded the Freedom Farms Cooperative.

The Freedom Farms Cooperative: A Vision for Economic Liberation

The Freedom Farms Cooperative (FFC) wasn’t just about growing crops—it was about growing self-sufficiency. The cooperative purchased hundreds of acres of land, which were collectively worked by members of the community. The goal was simple yet revolutionary: to ensure that no Black family in the area went hungry.

Key Initiatives of Freedom Farms:

Subsistence Farming: Families were given plots of land to grow their own food.

Collective Ownership: Unlike sharecropping, where Black farmers worked land owned by white landlords, the cooperative was owned and managed by its members.

Livestock and Poultry Programs: FFC raised livestock to provide meat and dairy products.

Affordable Housing Projects: The cooperative built homes for Black families, offering stability and security.

Hamer believed that food sovereignty was central to liberation. “If you give a hungry man food, he can live another day. But if you give him land, he can provide food for generations.”

Reflection: What does it mean to be truly self-sufficient in a society that denies you access to basic resources?

The Radical Act of Feeding Ourselves

The act of feeding oneself may seem mundane, but for Black communities in the South during the 1960s, it was revolutionary. The white power structure understood the importance of land and food, which is why they weaponized both to control Black people. Sharecropping kept families tied to plantations, and discriminatory lending practices prevented Black farmers from owning land.

By creating a cooperative model, Hamer not only fed families but also gave them agency. They could decide what to plant, how to distribute food, and how to support one another. The cooperative became a space of resistance and healing, where people could reclaim their dignity and humanity.

In today’s food justice movement, we see echoes of Hamer’s work. Community gardens, urban farming initiatives, and mutual aid networks continue her legacy by addressing food deserts and advocating for equitable food systems.

Challenges and Systemic Resistance

As with any liberation movement, Freedom Farms faced obstacles. The cooperative struggled to secure funding, as white-owned banks refused to provide loans. Local white residents attempted to sabotage their efforts, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture imposed restrictions that limited their growth.

Despite these challenges, Hamer persisted, drawing support from allies in the civil rights movement and beyond. Her determination to feed her community wasn’t just about survival—it was about making a statement: Black people deserve to own land, to nourish themselves, and to thrive.

Reflection: How can modern movements for food justice build on the legacy of the Freedom Farms Cooperative?

The Spiritual and Cultural Importance of Land

For Hamer and many others, land wasn’t just about economics—it was spiritual. In African and African diasporic traditions, the land is sacred. It carries ancestral memories, stories, and lessons. Working the land was an act of communion with those who came before and those who would come after.

Hamer’s vision for Freedom Farms was deeply rooted in this cultural understanding. She saw land as a tool for healing, where communities could reconnect with their ancestral knowledge and build a future free from the trauma of enslavement and sharecropping.

Her work reminds us that liberation is holistic. It’s not just about policy changes or legal victories—it’s about creating spaces where people can heal, grow, and build generational wealth.

Lessons for Modern Liberation Work

The Freedom Farms Cooperative offers several lessons for today’s liberation movements:

Collective Care: Liberation isn’t an individual pursuit. It’s about creating systems that uplift and protect entire communities.

Food Sovereignty: Access to food is a human right, not a privilege. Communities must have the power to grow and distribute their own food.

Resilience in the Face of Adversity: Hamer and her community faced countless obstacles, but they persisted. Their resilience is a testament to the power of collective action.

Reflection: How can we reclaim and protect land for marginalized communities today?

Why Fannie Lou Hamer’s Work Still Matters

In a world where food deserts disproportionately affect Black, Brown and poor communities, and where land ownership remains a significant barrier to economic stability, Hamer’s vision is more relevant than ever. The Freedom Farms Cooperative wasn’t just a response to hunger—it was a blueprint for liberation.

Today’s food justice advocates continue to fight for the right to grow, access, and distribute food on their own terms. Organizations working on urban farming, community-supported agriculture, and cooperative food systems are part of Hamer’s legacy.

Her work also challenges us to think beyond charity and toward empowerment. Feeding someone for a day isn’t enough—true liberation means creating systems where communities can sustain themselves for generations.

A 28-Day Journey Through Black Resistance and Liberation

Fannie Lou Hamer’s story is one of many lessons included in my 28-Day Journey Through Black Resistance and Liberation. This living document provides resources to explore Black history through the lens of resilience, defiance, and cultural pride. Each lesson is designed to not only educate but inspire action.

🌱 Join the journey today: Click Here

Let’s honor Hamer’s legacy by continuing to build systems of collective care and food sovereignty in our communities.

In solidarity and liberation,

Desireé B. Stephens CPS-P

Educator | Counselor | Community Builder

Founder, Make Shi(f)t Happen

Thankyou for including the recording of her singing!! You can hear the power and determination in her voice.

I’m enjoying this series immensely and learning a lot. As a white girl growing up in the 60’s and 70’s I never of most of these stories. Thankyou for bringing them to our attention. We need to hear them over and over in these extremely challenging times.

You are a treasure.

I was just looking at book about Freedom Farm. I am particularly interested because I have a friend who really wants to follow that model on her land. Having said that, I found a lot of books on Fannie Lou Hammer, but none about the farms in particular. Do you have book recommendations?