Industrialized Christianity: Labor, Bodies, and Class Oppression

Unraveling the Theological Roots of Exploitation and Reimagining Workplaces of Dignity

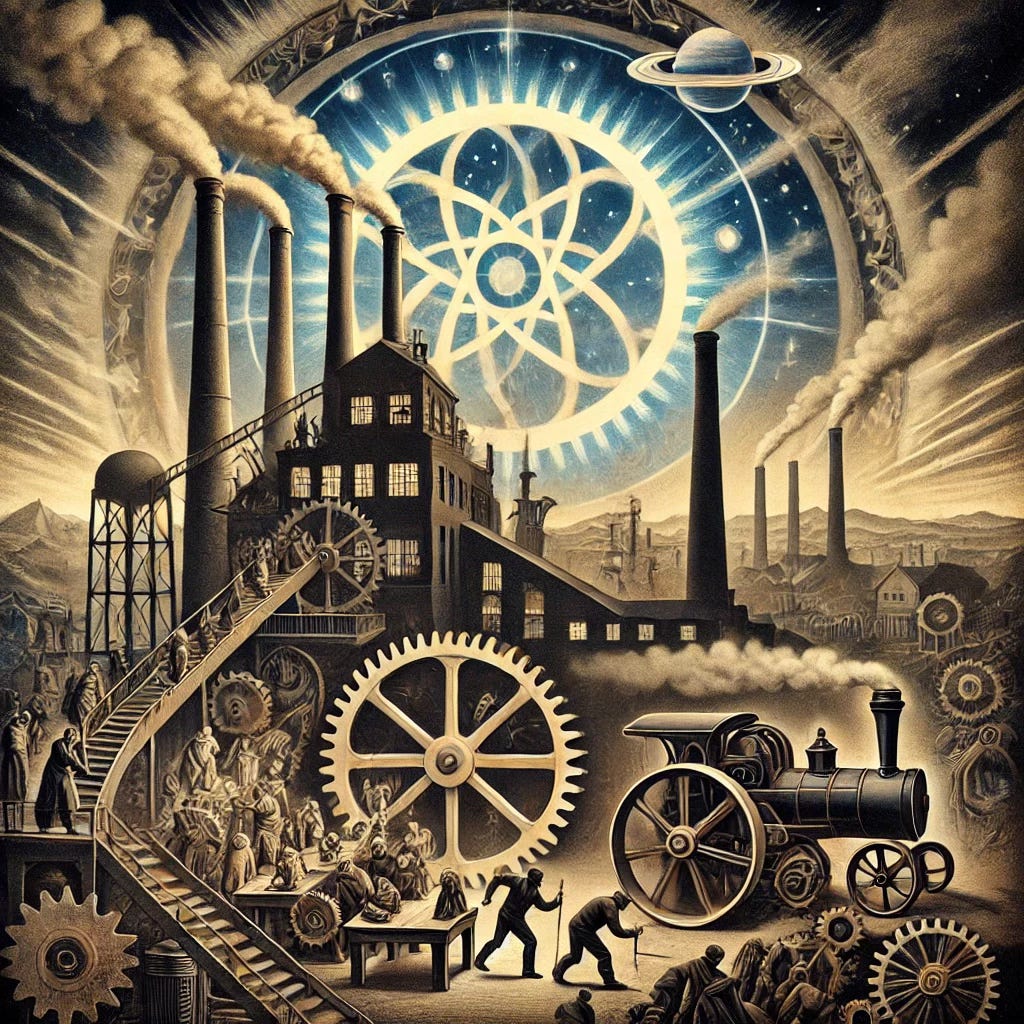

Introduction: The Price of Progress

How did Christianity—a faith rooted in love and liberation—become entwined with the machinery of labor exploitation? The Industrial Revolution wasn’t just a turning point for economies; it was a turning point for how we view work, human value, and community. In the relentless drive for progress, people became cogs in a system that prioritized productivity over humanity. Christianity, with its narratives about hard work, moral virtue, and scarcity, provided the spiritual fuel to power this shift—and justified the creation of racial hierarchies that assigned value to lives based on proximity to whiteness.

In this series, “I Want to Wish You an Eschatological Christmas,” we’ve explored Christianity’s role in shaping systems of oppression, from colonization to racial hierarchies. Now, we turn to the Industrial Revolution—a time when faith and capitalism merged to exploit bodies, entrench classism, and dehumanize labor. Together, we’ll uncover how these systems still shape our workplaces today and imagine new pathways rooted in collective care.

Calvinism and the Protestant Work Ethic: How Faith Shaped Labor

To understand the Industrial Revolution’s spiritual underpinnings, we must first understand Calvinism. Named after the 16th-century reformer John Calvin, this branch of Protestantism emphasized predestination—the belief that God has already determined who will be saved. Since people couldn’t change their fate, they began to view worldly success, particularly wealth and hard work, as evidence of being among the “elect.”

This belief evolved into what we now call the Protestant work ethic, which sanctified labor and framed poverty as a moral failing. It wasn’t just about working hard—it was about proving your worth to God.

Key Biblical Narratives:

Colossians 3:23-24: “Whatever you do, work at it with all your heart, as working for the Lord, not for human masters.” This verse was weaponized to frame labor as divine, even when it was exploitative.

Proverbs 10:4: “Lazy hands make for poverty, but diligent hands bring wealth.” This scripture reinforced the idea that poverty resulted from personal failure rather than systemic inequities.

Calvinism didn’t create capitalism, but it helped justify it. By equating hard work with morality and wealth with divine favor, Christian theology provided a framework for economic exploitation.

Work as Worship: The Moral Imperative of Labor

As the Industrial Revolution transformed economies, it also transformed people’s relationships with work. Factories demanded relentless output, and laborers—many of them children—were subjected to grueling conditions. Christianity sanctified this suffering, framing it as a form of worship and a moral duty.

The Virtue of Suffering:

Workers were encouraged to endure exploitation as a test of faith. Suffering was seen as redemptive, with the promise of heavenly rewards.

This narrative discouraged resistance, framing obedience to employers as obedience to God.

The Sin of Idleness:

Idleness was demonized, creating a culture where rest was seen as laziness. This mindset persists today in “hustle culture” and the glorification of overwork.

Racialized Labor:

Whiteness was constructed as the standard for civilized labor, while Black, Brown, and poor white bodies were relegated to exploitative, dehumanized work.

Enslaved Africans and colonized peoples were seen as divinely ordained laborers, reinforcing racial hierarchies that aligned work with moral and racial superiority.

Reflection Question:

How do these narratives about work and morality shape our modern attitudes toward labor and rest?

Industrial Labor and the Dehumanization of Bodies

The Industrial Revolution didn’t just exploit people—it commodified their bodies. Workers were valued only for their productivity, creating systems that dehumanized anyone who couldn’t meet capitalist standards.

Classism in the Factory:

The working class bore the brunt of industrialization, trapped in cycles of poverty and overwork.

Wealthy factory owners were framed as stewards of God’s resources, while workers were told to be grateful for their jobs.

Racial Hierarchies in Labor:

Black and Indigenous labor was systematically devalued, framed as necessary for the economic “progress” of white elites.

These racial hierarchies were justified by theological narratives that equated whiteness with divine favor and non-whitenes with servitude. (This often explains why poor white people feel like displaced millionaires)

Ableism and Fatphobia:

Industrial labor systems prioritized efficiency, excluding or exploiting disabled and fat-bodied individuals.

These narratives reinforced societal biases, framing nonconforming bodies as less valuable or less deserving of dignity.

Fear of Scarcity:

Theological narratives perpetuated the idea that resources were limited and competition was necessary. This fear justified exploitation and pitted workers against one another.

Reflection Question:

How do these historical labor systems continue to impact marginalized communities today?

Supremacy Culture at Work