The Exodusters Movement (1879): Building Freedom on New Soil

Black History Through the Lens of Liberation

In the years following the Civil War, as the promise of Reconstruction began to crumble under the weight of systemic racism, a movement of Black resilience took shape. Thousands of Black United States Americans, known as Exodusters, left the oppressive South in search of a better life on the open plains of Kansas and neighboring states. This migration wasn’t just about survival—it was a collective vision for freedom, self-determination, and the creation of thriving Black communities.

The Exodusters, named after the biblical “Exodus” of the Israelites from Egypt, understood that to achieve true liberation, they needed to leave behind the systems that sought to trap them in cycles of oppression. They weren’t just running from terror—they were running toward a new reality where they could build homes, grow food, own land, and live with dignity. (Doesn’t this theme sound familiar?)

The Broken Promise of Reconstruction

The Civil War may have ended slavery, but it didn’t end racial violence or oppression. During Reconstruction (1865–1877), Black United States Americans made significant political and economic gains, including holding public office and starting businesses. However, this period of progress was met with intense backlash from white supremacists.

By 1879, the message was clear: the South was determined to maintain white dominance, with or without slavery, and to that end, the South did, in fact, rise again. During Reconstruction, white violence was at an all-time high and became more strategic. White supremacists didn’t just rely on physical terror—they infiltrated positions of power through murder, intimidation, and organized campaigns of mayhem. Many local officials, policymakers, and law enforcement agencies became dominated by people with direct ties to groups like the KKK. These tactics laid the groundwork for the systemic oppression that persists today, with numerous current policymakers and institutions still linked to the legacy of white supremacy.

The rise of the Ku Klux Klan, along with restrictive laws known as Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws, made life in the South unbearable. Freedmen were terrorized through lynchings, forced labor contracts, and economic disenfranchisement. The federal government, under pressure to reconcile with Southern whites, began pulling back support for Black communities.

As an example here are some people with known affiliation to the Klan:

Robert C. Byrd (1917–2010): A U.S. Senator from West Virginia, Byrd was a former member of the KKK in the 1940s.

Hugo Black (1886–1971): Appointed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1937, Black had been a member of the KKK in the 1920s.

Edward Douglass White (1845–1921): Serving as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1910 to 1921, White was associated with the KKK during the Reconstruction era.

Reflection:

How can we truly feel safe in systems where individuals with documented ties to organizations like the KKK are often remembered as "good guys" or champions of civil rights? Figures like Robert C. Byrd, Hugo Black, and others have had their legacies softened or rewritten, despite their connections to white supremacist groups. This rewriting of history is dangerous—it teaches us that whiteness can be redeemed without accountability, while Black liberation continues to be scrutinized. If men with ties to the KKK are celebrated in history books and hold positions of influence, how can marginalized communities ever trust that these systems were designed to protect them? What must we dismantle and rebuild to ensure true safety and equity?

The Great Exodus: Why Kansas?

Kansas became a symbolic land of promise not just because it was a free state during the Civil War but because of its violent and transformative history during Bleeding Kansas (1854–1861). This period of bloody conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces determined whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state. The violence wasn’t confined to political debate—it was fought with bullets, torches, and sabotage. Black people, free and formerly enslaved, played crucial roles during this time, aligning themselves with abolitionist allies while continuing their long-standing resistance to slavery.

Figures like John Brown often dominate the narrative of Kansas’ fight for freedom, but the Exodusters’ migration proves that Black liberation was never dependent on any single white ally. Brown’s efforts, while significant, were one part of a much larger movement. For Black people, Kansas wasn’t a land gifted to them through the benevolence of abolitionists—it was a place they claimed through their resilience, hard work, and dreams of self-determination.

Entire families packed what little they had and made the journey by wagon, on foot, or by boat along the Mississippi River. They faced hunger, disease, and treacherous conditions, but they kept moving, driven by the dream of building something that could belong to them—a life free from the terror of Southern violence and economic exploitation.

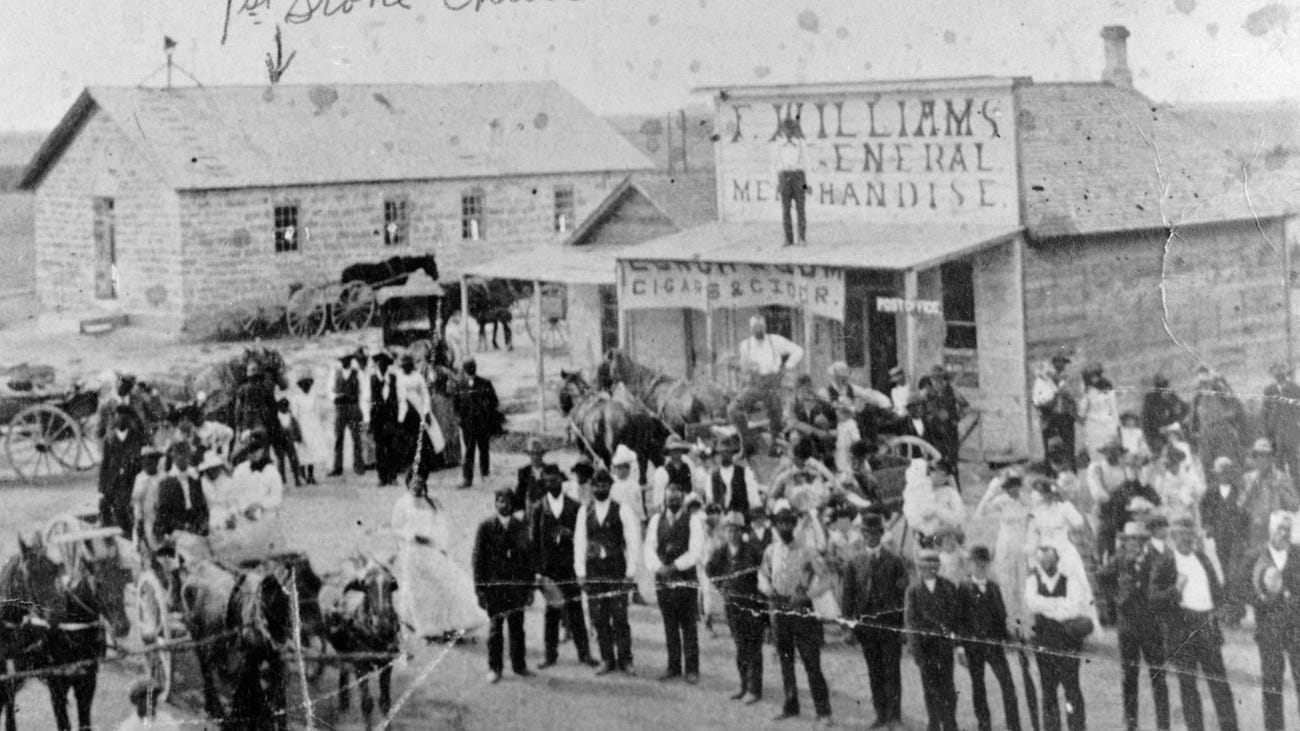

Some settled in towns like Nicodemus, Kansas, a thriving community built entirely by formerly enslaved people and their descendants. Nicodemus became a symbol of what Black communities could achieve, showcasing homes, schools, businesses, and churches that served as a testament to the Exodusters’ determination to not just survive but thrive.

The promise of Kansas wasn’t just about escaping oppression—it was about creating a future where Black people could own land, educate their children, and pass down generational wealth. The violence of Bleeding Kansas may have helped secure the state’s free status, but it was the Exodusters who made it a true land of Black promise, and until this very day, it is still home to their descendants.

Challenges on the Plains

Life on the plains was far from easy. Many Exodusters arrived with few resources, and the land they were given often required backbreaking work to make it farmable. They faced harsh winters, droughts, and discrimination from white settlers who resented their presence.

Despite these obstacles, the Exodusters persisted. They built homes, established churches, opened schools, and formed mutual aid societies to support one another. Their resilience turned barren land into self-sustaining communities where they could educate their children, worship freely, and farm their own land.

Actionable Step: Learn about the town of Nicodemus, Kansas, and reflect on what it meant for formerly enslaved people to build a self-sustaining community from scratch.

Community and Collective Resilience

What made the Exodusters’ movement remarkable wasn’t just their physical migration but their ability to form tight-knit communities rooted in mutual support. Churches, schools, and social clubs became the backbone of these settlements, providing spiritual and material support.

These communities reflected the values of interdependence, where the success of one family was seen as the success of all. This collective spirit helped them weather the many challenges they faced on the frontier.

Reflection: How can mutual aid and collective care help modern communities facing systemic challenges?

The Spiritual and Cultural Legacy of the Exodusters

The Exodusters carried with them more than just physical belongings—they carried ancestral wisdom, spiritual traditions, and a belief that their liberation was part of a larger divine plan. Many saw their journey as a modern-day Exodus, with Kansas serving as their “Promised Land.”

Spirituals and hymns were sung along the way, reinforcing the belief that God would guide and protect them. Their faith was not passive—it was active, intertwined with their determination to create a better life.

Reflection: How does spirituality play a role in sustaining resilience during periods of transition or hardship?

Why the Exodusters Movement Matters Now

The Exodusters’ journey wasn’t just about leaving behind physical danger—it was about rejecting a system that sought to limit their humanity and embracing the possibility of self-determination. Their legacy reminds us that when systems fail, we have the power to create our own paths, communities, and opportunities.

Today, as we confront modern forms of displacement, housing inequality, and systemic racism, the Exodusters’ story serves as a blueprint for collective resilience. It teaches us that liberation isn’t about waiting for systems to change—it’s about creating new ones that serve our communities.

Actionable Step: What lessons from the Exodusters can you apply in your community today? Consider how you can support or create mutual aid networks, cooperative housing initiatives, or community-led educational programs.

A 28-Day Journey Through Black Resistance and Liberation

The story of the Exodusters is one of many powerful lessons in my 28-Day Journey Through Black Resistance and Liberation. This living document provides families and individuals with resources to explore Black history through the lens of resilience, defiance, and cultural pride.

🌱 Join the journey today: https://desireebstephens.bio/shop/98d6f2f8-2827-4291-b29c-1ceaf77deaac

Together, let’s honor the Exodusters and all those who chose liberation, not because it was easy, but because it was necessary.

In solidarity and liberation,

Desireé B. Stephens CPS-P

Educator | Counselor | Community Builder

Founder, Make Shi(f)t Happen