The Irish in America—From Oppressed Immigrants to Political Power

Irish History Through the Lens of Rebellion and Resistance

When we think of Irish Americans today, we often see them as a deeply woven part of the American fabric—celebrated politicians, police officers, union leaders, and cultural icons. But the story of how the Irish became "American" is not one of simple assimilation. It is a story of resistance, labor, rebellion, and political strategy—a fight for survival in a land that first rejected them.

When the Irish arrived in America, they were treated as second-class citizens. But they organized, resisted, and eventually turned oppression into political power. This is the story of how the Irish fought for survival in the U.S.—and how the lessons of their struggle still resonate today.

Before Race, There Was Religion: The First Colonization Was Christianization

Before whiteness was codified as a racial caste system, Christianity was the original dividing line of empire.

The colonization of Ireland did not begin with land seizures or forced starvation—it began with Christianization. The British Empire, aligned with Protestantism, used religion as a tool of control, labeling Irish Catholics as heretics, savages, and enemies of “civilized” rule.

Christianization as Colonization: Just as the British weaponized Christianity to convert and control Indigenous peoples in the Americas, they first used the same tactics in Ireland.

Catholic vs. Protestant as the First Racial Divide: In early colonial hierarchies, Irish Catholics were not considered fully white. They were treated as inferior, lawless, and incapable of self-governance.

The Lowest Rung on the Pyramid: If whiteness is a pyramid scheme, Irish Catholics occupied the lowest rung, barely included in the structure at all.

It is crucial to recognize that Christianity was the gateway to racial caste systems. The same logic used to justify the oppression of Irish Catholics would later be expanded to enslaved Africans, Indigenous peoples, and non-Protestant Europeans.

This is the true origin of whiteness—it did not begin with race, but with religious hierarchy.

And when the Irish fled to America, they found themselves still at the bottom of the pyramid.

The Hidden Costs of Whiteness:

Let's Have The Conversation is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

From Forced Hunger to Forced Migration: The Irish Arrive in America

For centuries, the Irish had endured British rule, forced displacement, and systemic economic suppression. But the so-called "Great Famine" (1845-1852) was not just a natural disaster—it was a manufactured catastrophe, a genocide by starvation.

While the Irish people suffered mass starvation, Ireland was producing more than enough food to feed its population. However, the British government continued to export food, livestock, and other vital resources out of Ireland, prioritizing profits for English landowners over the survival of the Irish.

Grain, meat, and dairy products were shipped out daily, while the Irish starved in their own land.

British officials labeled the famine as a "natural event", denying aid and blaming the Irish for their own suffering.

Workhouses and relief efforts were deliberately insufficient, forcing people to either die in Ireland or flee overseas.

This was not a famine in the true sense—it was forced starvation. A calculated tool of colonial control designed to reduce the Irish population and break their resistance.

Over one million Irish people died from starvation and disease, and another two million were forced to flee—many boarding ships so overcrowded and diseased that they became known as "coffin ships."

For those who survived the harrowing journey across the Atlantic, arriving in America was not the fresh start they had hoped for. They were met with hostility, exclusion, and a campaign to make them permanent second-class citizens.

The Making of the "Savage Irish": Propaganda & Anti-Irish Sentiment in America

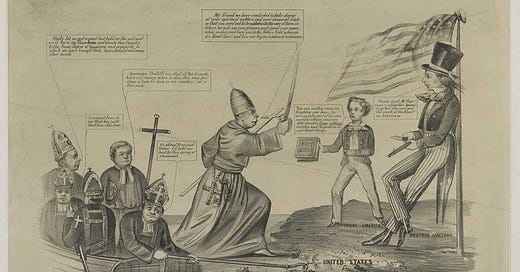

The Irish were seen as a threat to American society—both because of their sheer numbers and because they were overwhelmingly Catholic in a country dominated by Protestant elites. This xenophobia gave birth to one of the most aggressive anti-immigrant propaganda campaigns in American history.

The "Drunken, Violent, and Lazy" Narrative

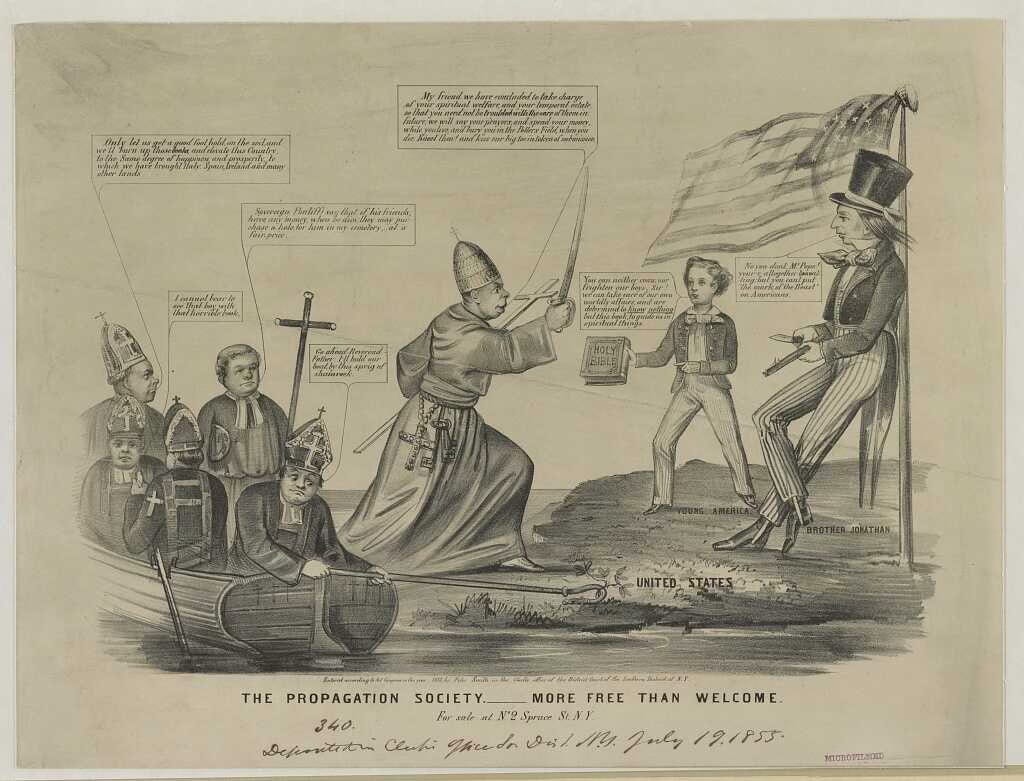

Newspapers, political cartoons, and speeches painted the Irish as drunkards, criminals, and inherently inferior to Anglo-Americans. They were depicted as wild, ape-like creatures, more animal than human.

Thomas Nast’s political cartoons often portrayed the Irish as violent brutes with exaggerated, simian features—depicting them as closer to apes than civilized men.

The phrase “No Irish Need Apply” (NINA) was not just a myth. It was a very real sign posted on businesses across the country, barring Irish workers from employment

Irish immigrants were called "white negroes", implying that they were racially inferior and more akin to enslaved Africans than to other Europeans. This is called “scientific racism”

This racialized depiction was intentional—it sought to dehumanize the Irish, justify their exclusion from jobs, and suppress their political power.

The Catholic Threat: Accusations of Disloyalty

Anti-Irish sentiment was also deeply tied to anti-Catholicism. Many Americans, especially the nativist Know-Nothing Party, feared that Irish Catholics would pledge their loyalty to the Pope over the U.S. government.

The Know-Nothing Party (1850s) pushed conspiracy theories that Irish immigrants were part of a secret Catholic plot to overthrow democracy.

Catholic churches were burned to the ground in cities like Philadelphia and Boston during anti-Irish riots.

The Irish were accused of stealing elections through "machine politics," a claim that ignored how democracy actually worked for marginalized groups.

One thing is for sure, nothing is new under the sun in colonization.

Violence Against the Irish: Riots & Lynchings

Hatred for the Irish wasn't just expressed in words—it often turned violent.

The Philadelphia Nativist Riots (1844) saw Protestant mobs attacking Irish neighborhoods, setting Catholic churches on fire, and killing Irish residents.

The Bloody Monday Riots (1855) in Louisville, Kentucky left at least 22 Irish immigrants dead as mobs torched Irish homes and businesses.

Lynchings of Irish immigrants were not uncommon, especially in the South, where they competed for labor with enslaved Black workers.

The Irish Fight Back: Labor Movements & Political Power

Despite relentless discrimination, the Irish refused to be kept at the bottom of society. They used two powerful tools of resistance: labor unions and political organization.

Labor Unions & The Irish Worker

The Irish were often forced into the most dangerous, low-paying jobs—digging canals, working in factories, and laying railroad tracks. But they organized.

The Molly Maguires, a secret society of Irish coal miners, used direct action and even sabotage to fight for workers’ rights in the 1860s and 1870s.

The Irish played a major role in founding the Knights of Labor, one of the first major unions in the U.S.

By the late 19th century, Irish labor leaders helped push for laws protecting workers from exploitation.

From Outcasts to Mayors: The Irish Political Machine

One of the biggest ways the Irish broke into the system was by seizing political power through urban political machines.

Tammany Hall in New York City, once dominated by Protestant elites, was taken over by the Irish. Through patronage and voter mobilization, they built a powerful political network that helped Irish immigrants gain jobs, housing, and protection.

Irish Americans became police officers, firefighters, and city officials, embedding themselves into American civic life.

By the early 20th century, Irish mayors ran cities like New York, Boston, and Chicago, proving that they had successfully transformed from outcasts into political power players.

The Black-Irish Connection: Choosing Whiteness Over Solidarity

The Irish and African American experiences were not identical, but they were deeply connected.

Both groups were treated as second-class citizens and were frequently pitted against each other for low-wage labor.

The Irish were called "white negroes", a term that acknowledged their racial liminality—but also hinted at the choice they would be given: assimilate into whiteness or remain oppressed.

In the early days, Irish and Black workers sometimes found solidarity—especially in labor movements and urban struggles.

But ultimately, many Irish immigrants chose whiteness.

Unlike African Americans, the Irish had a path to whiteness—a choice they could make to distance themselves from Black people in exchange for power. Many did exactly that.

The Irish became police officers and enforcers of racial hierarchy.

They sided with white supremacy to gain acceptance.

They built their political power on excluding Black workers from unions and opportunities.

Frederick Douglass saw this transformation in real time and warned the Irish:

"The Irish, who, at home, readily sympathize with the oppressed everywhere, are instantly taught when they step upon our soil to hate and despise the Negro... Sir, the Irish-American will one day find out his mistake."

— Frederick Douglass, May 10, 1853

Final Reflection: Moving Forward in Solidarity After Betrayal

The story of the Irish in America is one of resistance, survival, and adaptation. They arrived as an unwanted, despised group, facing intense discrimination and propaganda that sought to keep them powerless. But they fought back—through labor movements, political organization, and community solidarity.

However, their eventual assimilation into whiteness came at a cost. In gaining full citizenship and political power, many Irish distanced themselves from other oppressed groups—choosing security over solidarity.

This is a painful truth. But it is a truth that must be spoken.

The Irish who had once been oppressed alongside Black people, who had suffered under British rule, who had fought back against empire—many of them ultimately turned their backs on the very people they once stood beside.

This is what whiteness as a system does. It forces people to make a choice: stand in solidarity with the oppressed, or align with power.

And many Irish immigrants, faced with the very real threats of poverty and exclusion, chose power.

So where do we go from here?

How do we move forward in solidarity after such betrayal?

How do we heal the wounds that history has left behind?

How do we build trust in movements that demand both truth and accountability?

The first step is acknowledgment. Accountability is owning the truth. It is not about shame or guilt—it is about being honest about what happened. The Irish, like many immigrant groups, were given a choice, and too many of them chose the wrong side of history.

But accountability is only the beginning.

From accountability, we move to repair.

We recognize the harms done—not just in history but in the present, where systems built on racial and economic hierarchy still function.

We reject the false promise of whiteness, understanding that it was never about inclusion—it was about control.

We return to the radical solidarity that once existed—where Irish and African people fought together, bled together, and resisted empire together.

We commit to justice that is rooted not in assimilation but in shared liberation.

Because history is not just about remembering the past—it is about how we choose to act in the present.

And if there is one lesson the Irish should carry from their history, it is this: freedom at the expense of others is not true freedom.

We cannot undo the past. But we can choose a different future.

One that rejects assimilation in favor of true belonging.

One that rejects power over others in favor of power with others.

One that understands that solidarity is not just a moral choice—it is a survival strategy.

Because as long as empire exists, as long as oppression thrives, as long as systems continue to divide and dehumanize—none of us are truly free.

It is time to return to what was once known.

It is time to reclaim true solidarity.

Tomorrow’s Lesson: Bacon’s Rebellion & The Invention of Whiteness

The Irish and African laborers once stood together. But after Bacon’s Rebellion (1676), the ruling class created a system that divided them—forever changing race and class in America.

Join us as we explore how whiteness was invented to keep people divided.

📖 Support This Work: Keep History Alive

This article is free for March, but after that, it will be available only through 59 Days of Resistance: A Journey Through Black and Irish Liberation.

👉 Get the full curriculum here: 59 Days of Resistance Guide

Become a paid subscriber to continue learning. If finances are a barrier, email me at Scholarships@DesireeBStephens.com.

Because remembering is resistance.

And resistance is how we reclaim what was stolen

In solidarity and liberation,

Desireé B. Stephens CPS-P

Educator | Counselor | Community Builder

Founder, Make Shi(f)t Happen