The Red Summer (1919): When Black Resilience Faced White Rage

Black History Through the Lens of Liberation

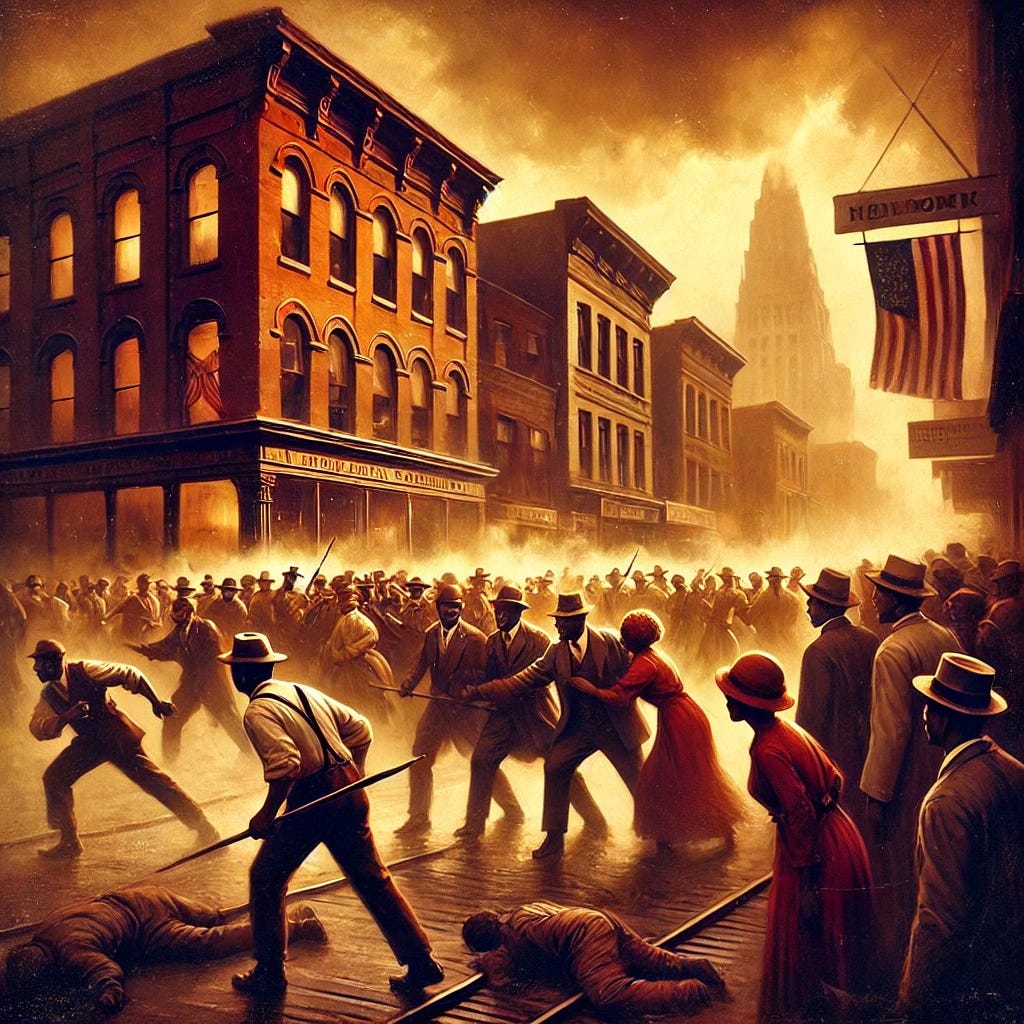

The summer of 1919 wasn’t just a season of warmth—it was a season of bloodshed, resistance, and resilience. Known as the Red Summer, this period saw a wave of white supremacist violence erupt across the United States, targeting Black communities with deadly precision. The violence wasn’t confined to a single city—it stretched across more than 30 locations. From Chicago to Washington, D.C., from Elaine, Arkansas, to Omaha, Nebraska, white mobs attacked Black neighborhoods, burned homes, and lynched men and women, determined to enforce their dominance in the wake of World War I.

But in the midst of this terror, Black communities didn’t just endure—they fought back, physically, politically, and culturally. The Red Summer became a defining moment in the long struggle for civil rights, showing the world that Black Americans would not be passive in the face of violence.

This was not the first nor the last time white rage followed Black progress, but it was one of the most visible and coordinated assaults on Black freedom.

Let’s explore why this period was pivotal in shaping future movements for civil rights and why the narratives of Black self-defense remain essential today.

The Aftermath of War: Black Veterans Return Home

When World War I ended in 1918, thousands of Black veterans returned home, many of whom had fought bravely for the United States in Europe. They came back with a renewed sense of dignity and entitlement to the rights they had been denied before the war. Having fought for democracy abroad, they expected to experience it at home.

However, the racial climate in the U.S. was anything but welcoming. White Americans, particularly in the South and urban Northern areas, viewed the return of empowered Black men as a threat to the social order. This tension was exacerbated by the migration of thousands of Black people to Northern cities during the Great Migration (1910-1970), seeking better jobs and escaping the racial terror of the South.

Black soldiers returned home to a country that still treated them as second-class citizens. Their service abroad was met with hostility rather than gratitude, as white Americans feared the growing sense of Black pride and independence.

Economic Competition: Many Black families had migrated North during the Great Migration, seeking better opportunities in cities like Chicago and Detroit. But their success in gaining jobs and housing was seen as a threat by white workers who blamed them for economic instability.

Racial Tension: The growth of Black communities in urban areas led to resentment from white residents who were unwilling to share public spaces or resources.

Political Activism: Organizations like the NAACP were becoming more prominent, and Black leaders were demanding full citizenship rights, including the right to vote, equal education, and protection from violence.

These tensions exploded during the Red Summer, with over 25 documented race riots occurring between May and October of 1919.

Reflection: How do we reconcile the fact that Black people were expected to fight for the same country that denied them basic human rights?

The Catalyst for Violence: Economic Competition and White Fear

White resentment toward the growing Black population was stoked by fears of job competition and changing racial dynamics. In cities like Chicago and Washington D.C., labor strikes and housing shortages increased tensions. White mobs, often with the support of local police, attacked Black neighborhoods, burning homes, assaulting residents, and destroying businesses.

In Elaine, Arkansas, a Black sharecroppers’ union meeting became the site of one of the most violent massacres of the Red Summer when white mobs, with the assistance of local law enforcement, slaughtered over 200 Black men, women, and children. The event underscored how any form of Black organization or resistance—whether through unions, social clubs, or economic self-sufficiency—was viewed as a threat to white supremacy.

Actionable Step: Research the Elaine Massacre and reflect on how economic independence among Black communities was targeted as a form of resistance.

Black Resistance: Fighting for Their Lives and Communities

During the Red Summer, Black people didn’t just defend their homes and communities—they defended their dignity and future. Armed groups of Black men and women, including many veterans, organized to protect their neighborhoods from white mobs. In Chicago, where the violence lasted for nearly two weeks, Black residents formed patrols and barricades, fighting back with whatever weapons they could find.

In Elaine, Arkansas, Black sharecroppers were meeting to organize for fair wages when they were attacked by white mobs. What followed was one of the deadliest race massacres in U.S. history, with over 200 Black men, women, and children killed. Despite the horror, survivors of the massacre fought back in court, challenging the systemic violence that sought to silence them.

The Red Summer demonstrated that Black people were not passive victims of white aggression—they were active agents of their liberation, even when the odds were stacked against them.

Reflection: How does self-defense fit into the broader framework of liberation movements? Why is it important to acknowledge that resistance can take many forms, including armed defense?

The Role of Media: Inciting Violence or Amplifying Resistance

The role of media during the Red Summer cannot be ignored. White-owned newspapers often incited violence by publishing inflammatory articles about “Negro uprisings” or alleged assaults on white women. These false reports fueled the violence and justified the actions of white mobs.

In contrast, Black-owned newspapers, such as the Chicago Defender and the Baltimore Afro-American, provided critical coverage of the violence and highlighted the acts of Black resistance. These publications were instrumental in spreading awareness and organizing national support for the victims.

Actionable Step: Explore the role of Black media during the Red Summer and its impact on the fight for civil rights. How can independent media today play a similar role in addressing systemic injustices?

The Aftermath: Setting the Stage for the Civil Rights Movement

The Red Summer didn’t end with a clear victory for either side. While Black communities faced significant losses in lives and property, the events also marked a turning point in how Black resistance would be viewed moving forward. It was a lesson in collective resilience and the power of self-defense, and it laid the groundwork for future movements, including the Harlem Renaissance and the Civil Rights Movement.

The memory of the Red Summer inspired Black leaders like Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Du Bois, and others to continue the fight against lynching, segregation, and racial violence.

Reflection: How can remembering the Red Summer help us understand modern forms of racial violence and the importance of organizing in response to it?

The Spiritual and Cultural Legacy of Resilience

Throughout the Red Summer, spirituals, hymns, and cultural rituals provided solace and strength to Black communities. Churches were often the only safe spaces for organizing and healing. The resilience displayed during this period wasn’t just physical—it was spiritual, cultural, and emotional.

Many families passed down stories of the Red Summer as lessons in resilience, reminding future generations that survival is an act of resistance in itself.

In the face of violence, cultural resilience was just as vital as physical resistance. One of the most powerful cultural weapons during this time was “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” often referred to as the Black National Anthem. Written by James Weldon Johnson and set to music by his brother J. Rosamond Johnson, the song became a rallying cry for hope and resilience.

During the Red Summer, this song was sung at protests, church services, and community gatherings, offering comfort and reminding Black communities of their collective strength. Its lyrics encapsulated the endurance of a people determined to overcome:

"Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us,

Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us;

Facing the rising sun of our new day begun,

Let us march on till victory is won."

The power of “Lift Every Voice and Sing” wasn’t just in its words but in the way it connected generations of Black Americans, linking the struggles of the past with the hopes of the future.

Reflection: How can cultural tools, such as songs and stories, help sustain resilience and inspire collective action in the face of adversity?

Why the Red Summer Matters Today

In the face of ongoing police violence, housing discrimination, voter suppression, and economic disparities, the Red Summer remains more than a historical reference—it’s a mirror reflecting many of the same themes we are grappling with today. White rage following Black progress, organized violence against marginalized communities, and the criminalization of Black self-defense are not relics of the past—they are the undercurrents of our present.

When Black liberationists speak, organize, and educate, they are not just theorizing—they are drawing from a deep well of historical awareness. We have seen these cycles before. We know the patterns, because our ancestors endured them, resisted them, and handed down their wisdom. This historical awareness is what allows us to anticipate, respond, and push forward, even when the world insists that progress is impossible.

The Red Summer reminds us that self-defense is not just a right—it is a necessity in systems designed to harm marginalized communities. But self-defense doesn’t always look like armed patrols or barricades; it also looks like organizing mutual aid networks, protecting community spaces, and preserving the stories of resistance that mainstream history often tries to erase.

We are often living in time loops, repeating cycles of progress and backlash. But through the lessons of events like the Red Summer, we see that those loops don’t have to define us—they can inform us. They remind us that liberation is a continuous process, not a single moment in time. By recognizing the cycles, we gain the power to disrupt them.

Reflection: How can we break free from the cycles of progress and backlash, and how can non-Black allies better listen to the historical knowledge that Black liberationists bring to the fight for justice?

The Red Summer isn’t just a historical event—it’s a blueprint for resilience, self-defense, and collective action that continues to guide us today.

A 28-Day Journey Through Black Resistance and Liberation

The story of the Red Summer is one of many lessons included in my 28-Day Journey Through Black Resistance and Liberation. This living document is continuously updated with lessons, discussions, and resources designed to empower individuals and families to explore Black history beyond the trauma, centering resilience, defiance, and victory.

🌱 Join the journey today: Click Here

Together, let’s remember the lessons of the past to build a liberated future.

In solidarity and liberation,

Desireé B. Stephens CPS-P

Educator | Counselor | Community Builder

Founder, Make Shi(f)t Happen

It disturbs me that 200 people were slaughtered and I never heard about this in a single history class I ever took. This is a tremendously significant piece of history! I'd did learn about lynchings, Malcom X and MLK, but not this. I'm pondering. Perhaps the supremacy story prefers us to be able to think of white violence at a fringe thing, not relevant to all of us, not something that can grow into a Red Summer?

Really appreciate these lessons in Black History. They are deeply inspiring. I pray there will come a day when these stories are taught in schools and included in history books. The current political climate can lead one to despair but work like yours gives me hope.